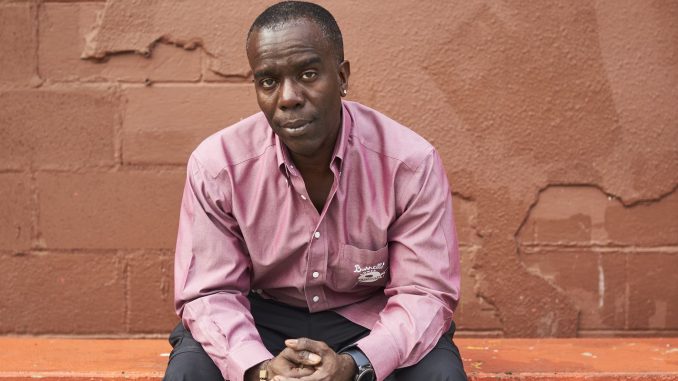

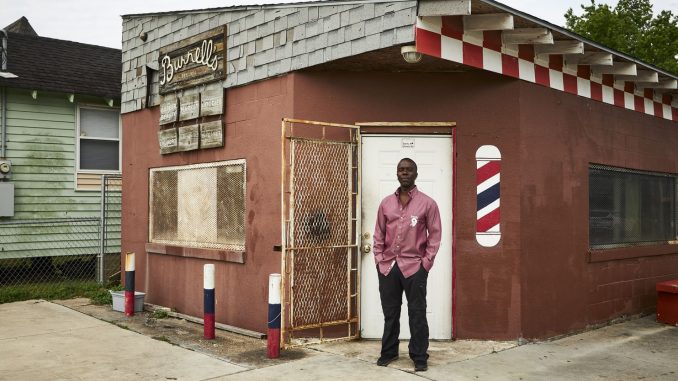

I know every person who comes into this store, and they know me. Burnell’s Market. It’s my name above the door. These are my neighbors, but now we’re eyeing each other like strangers, paranoid and suspicious. “Don’t stand so close.” “Don’t breathe too heavy.” “Just drop the groceries in the trunk and walk away.” Some people have started sliding money back and forth across the counter with a plastic spoon.

Everybody’s scared of everybody in a grocery now. There’s so much fear, and I get it. I’m scared, too. But what bothers me more is the desperation.

This is the only fresh grocery in the Lower Ninth Ward of New Orleans, so pretty much everybody’s a regular. They come for cigarettes or a biscuit on their way to work. Its mostly tourism jobs down here — Bourbon Street, the big hotels, and restaurants downtown, and those places have closed up in the last month. At least half my customers have lost jobs. They come to the register counting food stamps, quarters, and dimes. I keep telling them, “It’s okay. I’m not in a hurry. Take your time. Stop apologizing.” I had somebody barter me last week over a 70-cent can of beans. I used to sell two pieces of fried chicken for $1.25, and I cut it to a dollar.

We have an ATM in the store, and I watch people punching in their numbers, cursing the machine, trying again and again. It gives out more rejection slips than dollar bills. Some of these people don’t have any savings. There’s no fallback.

Last week, I caught a lady in the back of the store stuffing things into her purse. We don’t really have shoplifters here. This whole store is two aisles. I can see everything from my seat up front. So I walked over to her real calm and put my hand on her shoulder. I took her purse and opened it up. Inside she had a carton of eggs, a six-pack of wieners, and two or three candy bars. She started crying. She said she had three kids, and her man had lost his job, and they had nothing to eat and no place to go. Maybe it was a lie. I don’t know. But who’s making up stories for seven or eight dollars of groceries? She was telling me, “Please, please, I’m begging you,” and I stood there and thought about it, and what am I supposed to do?

I said: “That’s okay. You’re all right.” I let her take it. I like to help. I always want to say yes. But I’m starting to get more desperate myself, so it’s getting harder.

The first time in my life I let a customer float on credit was four weeks ago. It was a young guy who comes by most days to buy a few things, or just to sit outside with me on the milk crates and chop it up. He got home from the military a few years back, and I was in the Army, so we have that in common. Good guy. He’d been working as a cook downtown, and last month his restaurant closed up. He asked if he could come work for me.

I operate on a shoestring. It took every dollar I had to open this place after Hurricane Katrina. I’ve robbed Peter to pay Paul so many times that Peter’s got nothing left. So I had to tell him, “I already have a cook, and I’m barely paying him. I can’t afford two.” But this guy, he was hurting. He needed something to eat. He picked up four cans of tuna, a Sno-Ball, and laundry detergent. He told me he was good for it as soon he gets his unemployment check, and I trust him. I rang it up for eleven dollars. I took out a notebook that I usually keep near the register and started a little tab.

That notebook kept coming back out. Next it was Ms. Richmond. She did housekeeping at a hotel and lost that. Her tab was $48. Then it was a lady who shucks oysters downtown. She’s got a big family to take care of, so she’s at $155. Then there’s another guy who I deliver to, since he’s bedridden, and I showed up with two bags and he had nothing to give me. So he’s at $54.80.

This has gone from a grocery store to a food pantry. That’s how I’m feeling.

And what am I supposed to say? I don’t blame any of these people. I like them. Some of these customers, I love. I truly do. They’re getting by however they can. It’s not their fault. It’s not like they’re asking me for handouts on gin or beer. I don’t sell alcohol. I won’t give loans on cigarettes. What they need is milk, cheese, canned goods, bread, toilet paper, bleach, baby wipes. It’s basics — the basic essentials. One elderly guy tried to start a tab for three dollars of snacks for his grandchildren, so I gave him the snacks. Another lady said she lost her job at a nightclub downtown, and she tried to proposition me for $20 even though my wife was standing right there working at the register. I gave her the $20 and she left.

I’ve got 62 tabs in the book now. From zero to 62 in less than a month. It’s page after page of customers on credit. I’m out almost $3,000 so far. I know that might not sound like much, but at a store like this it’s my electric bill, my water bill, the mortgage on my house. I never missed a mortgage payment in my life until April 1st came and went, and now this virus has me calling around and asking for forgiveness, too. I’m paying one of my employees with free breakfast. I’m maxed on bills. I’m doing my best to keep this place open. Everybody here is waiting on unemployment checks and stimulus payments to keep us going, but let’s be real. Some of these losses aren’t coming back. I know how this goes. I lived in a FEMA trailer for three years after Katrina. I went from having 48 neighbors on my block to having three. They can talk all they want about how we’ll bounce back and this will all be behind us before we know it, but not everybody bounces back. Some people are already standing in quicksand. There might be a recovery on Bourbon Street, but when will it show up here? Recovering can take forever.

Sorry. I try to be optimistic. I try not to be angry. There’s no use in it, and it’s not my personality.

My customers come to the store because it’s a happy place, and this community deserves something good. I’ve got music blaring out front, always upbeat, drawing people in. I have candy and cold treats for the kids that are out of school. I’m running out of some things now that it’s getting so tight. I’m low on rice and sugar, but I hustle to fill this store. I say to my customers: “Tell me what you want and I’ll stock it.” They’re grateful for this place. But right now most everybody coming into the store is terrified. They’re upset. They’re mad. The reality right now is this virus is hitting the black community harder. It’s the same old story.

Life in this neighborhood is an underlying condition: hard jobs, long hours, bad pay, no health insurance, no money, bad diet. That’s every day. They have disabilities. They have high blood pressure, breathing problems, diabetes. Before I opened, this part of the city was a food desert. The easiest way to get fresh produce was to take three buses to the Walmart in Chalmette. I gave free blood-pressure checks when I opened, and not because it was good for business. Cigarettes are a big seller. Candy and cold drinks go quick. I tell people, “You only live one life. You’ve got to look after it.” But fruits and veggies are expensive. If you’re hungry, are you spending that dollar on an onion, or on nachos with chili cheese? We were made more vulnerable to this virus down here because of what we’ve had to deal with. Wearing a mask won’t protect us from our history.

All of us know people now who are sick, or worse. My mom was exposed and quarantined for two weeks. I had a guy in the store the other day talking about how his sister was going on a ventilator. We lost one of our customers a few days ago, Mr. Lewis. He ran a free museum on black culture. Sixty-eight years old, and that’s that.

There’s another lady who lived two blocks from the store. She’d been coming almost every week since I opened, but she’d been having a hard time. She lost her income and needed groceries, so we started her on a tab. Then she caught the virus, and I delivered more groceries to her porch.

She died last week, and a few days later, I went into the book to look at her tab. There are a few accounts closing like that now, and probably more coming. Hers was 72 dollars and 14 cents. I found her name and drew a line through it.